Binary Room: Implementation of a RISC-V to ARM Translator

Published:

by Samir Rashid, Anthony Tarbinian, David Tran (equal contribution)

This paper is best read as a pdf in its original typesetting. In this paper, we describe our experience going from idea to implementation of a binary translator.

Abstract

Binary Room is a static binary translator from RISC-V to ARM binaries. It targets userspace applications and supports a subset of the RISC- V instruction set. We can translate applications that perform memory operations, control flow and system calls. This report outlines the details of the implementation along with challenges we ran into.

1. Introduction

Binary Room statically translates binaries from a subset of the riscv64 to aarch64 instruction set architectures (ISA). We support arbitrary 64-bit userspace binaries, which can include function calls and syscalls. We support a subset of RISC-V instructions which perform arithmetic, memory operations, control flow, and system calls. First, Section 3 provides an overground of our design decisions. Next, Section 4 provides an overview of the aspects of our implementation. We outline the high-level flow of binary translation, along with the difficulties in writing each module of the code (Section 5). Lastly, we evaluate Binary Room's input and output binaries (Section 6).

2. Background

RISC-V is the future of open computing. Binary translation is a form of emulation which enables running binaries from other architectures. To smooth the transition to the RISC-V ISA, we present Binary Room, a tool to run unmodified RISC-V binaries on ARM. Binary Room statically translates binaries without the need for any hardware virtualization extensions.

Our translator is inspired by Apple’s x86 to ARM binary translator, Rosetta 2. Similarly, our tool transparently converts userspace binaries from riscv64 to aarch64 instructions. Binary translation has proved to be a flexible and efficient approach for ensuring binary compatibility (A Comparison of Software and Hardware Techniques for X86 Virtualization, 2006).

3. Design

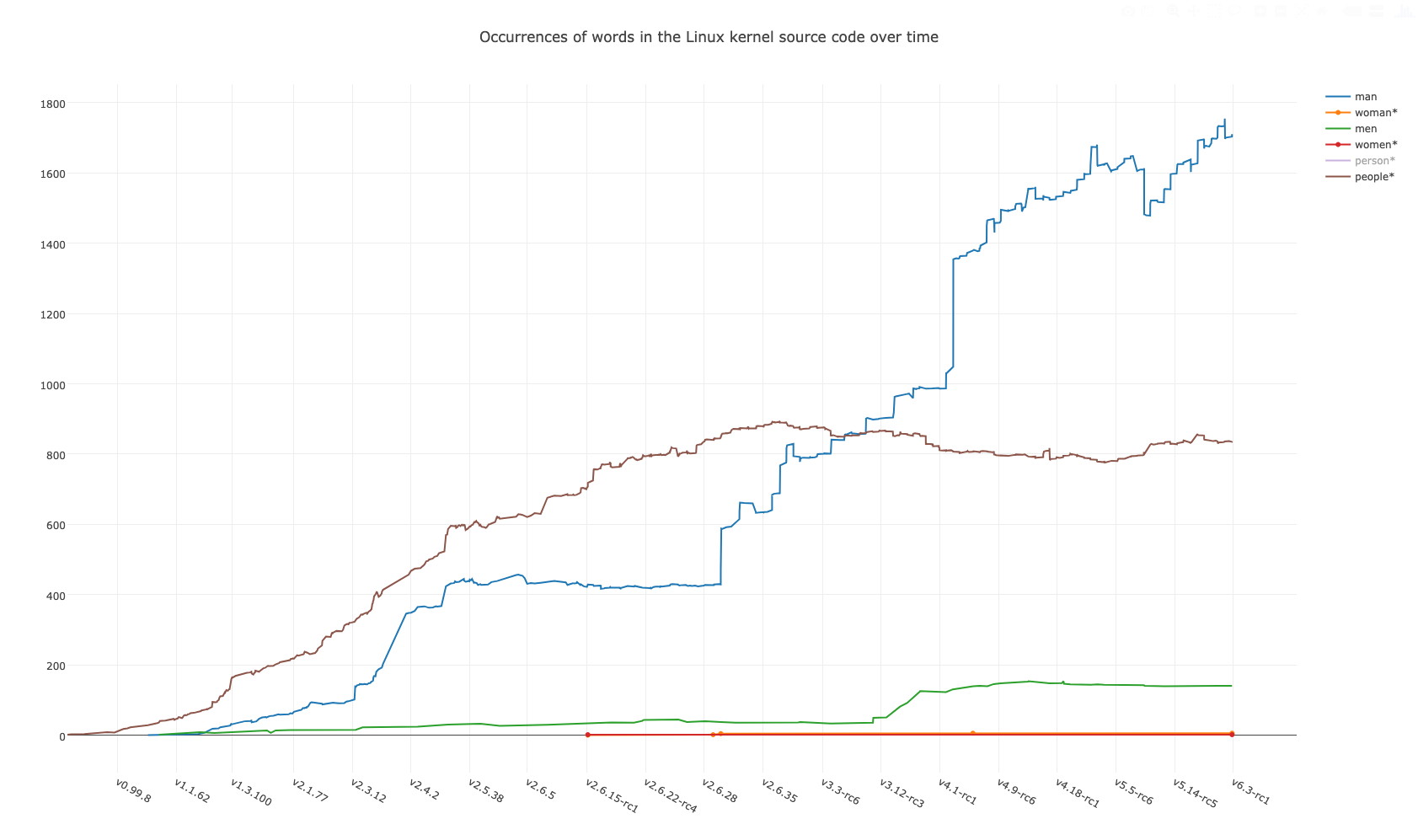

At a high level, Binary Room operates by consuming a list of RISC-V instructions, iteratively translating each instruction from RISC-V to ARM, converting the ARM instructions to an ARM assembly file, and forming an ARM executable.

Binary room operates at the assembly level, so there are a few steps before producing an executable binary. We assemble the assembly code into an object. Then, we take the object code and link it into the final binary file. On Linux, where we performed the bulk of our testing, this was an ELF file (Tool Interface Standard (TIS) Executable and Linking Format (ELF) Specification Version 1.2, 1995).

4. Implementation

4.1. Representing Instructions

We exploited the Rust type system to encode information about the RISC-V and ARM instructions (RISC-V Instruction Set Specifications, 2019). Specifically, we extensively used Rust's algebraic data types, enums, throughout our codebase.

Parsing the assembly into the Rust type system provides guarantees of the arguments to instructions at compile time. There are many steps that can go wrong, which makes debugging challenging. Parsing, translation, and runtime errors are examples of issues during development. One difficulty is that to support general binaries, you must implement the entire source and destination instruction set and must also encode all the alignment, calling convention, and syscall constraints. To deal with this complexity, we introduce Panic Driven Development (PDD). PDD ensures that binaries we cannot translate fail at the parsing stage. The code will be unable to encode instructions it cannot translate by the design of the enum. This strategy prevents debugging malformed assembly output.

Each enum variant encodes the exact instruction and the types of its arguments.

pub enum RiscVInstruction {

/// add register

/// either add or addw

/// (addw is 32 bits on 64 bit riscv)

///

/// `x[rd] = sext((x[rs1] + x[rs2])[31:0])`

#[strum(serialize = "add")]

Add {

// dest = arg1 + arg2

width: RiscVWidth,

dest: RiscVRegister,

arg1: RiscVRegister,

arg2: RiscVRegister,

},

// Copy register

// `mv rd, rs1` expands to `addi rd, rs, 0`

#[strum(serialize = "mv")]

Mv {

dest: RiscVRegister,

src: RiscVRegister,

},

…

}

RISC-V instructions

For the ADD instruction case, the width field specifies whether the instruction is invoked with double or word register width. The arguments to the instruction are defined in another enum which represents CPU registers.

pub enum RiscVRegister {

#[default]

#[strum(serialize = "x0")]

/// Hard-wired zero

X0,

#[strum(serialize = "ra")]

/// Return address

RA,

…

}

Our instruction type supports ARM instructions that are not present in the RISC-V ISA. Notably, conditional branching in ARM requires a CMP instruction to set condition flags based on registers operands. For example, to branch to the label foo if x1 != x2, we must first cmp x1, x2 and then conditionally branch bne foo. RISC-V handles conditional branches by taking additional operands in the branch instruction, e.g. bne x1, x2 foo. During translation, Binary Room may output multiple ARM instructions for a given RISC-V instruction.

One limitation of our enum is that we must manually parse from the disassembled binary into the Rust enum. We prioritized implementing the binary translation and did not finish writing a complete parser. Encoding the enum into assembly is straightforward as we use Rust's formatter to convert the list of instructions into validly formatted assembly.

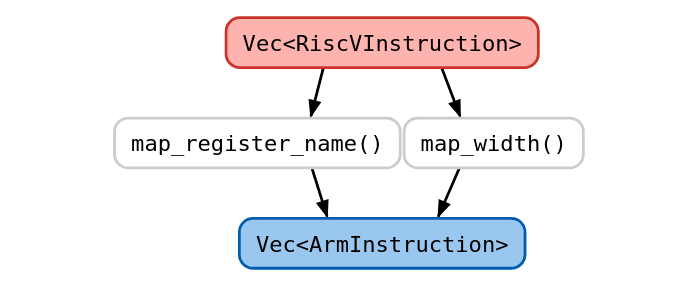

4.2. Variable Width ARM Registers

One feature we encode in the type system is register width. Both ARM And RISC-V have 32 general-purpose registers. However, ARM registers can be used as either 32-bit or 64-bit registers. ARM registers are indicated by the first letter of the register name in the assembly. An “x” indicates 64 bits of a register and a “w” indicates the least significant 32 bits of a register (Registers in Aarch64 State, 2024). This variation means that translation must account for the register width that RISC-V instructions specify and output an ARM instruction with the correct register widths.

We ensured correctness of the binary translation by unit testing simple cross-compiled RISC-V programs. Our tests automatically run in GitHub actions on every commit, and can be run locally using cargo, the Rust build system.

4.3. Register Mapping

During instruction translation, we had to be cautious in how we translate the registers in use. Some registers are not general purpose and have semantic meanings, such as the stack pointer (ARM Register Names, 2024). Other registers are expected to have some meaning after function calls, such as the return register. We needed to be mindful of these invariants and avoid overwriting any important state.

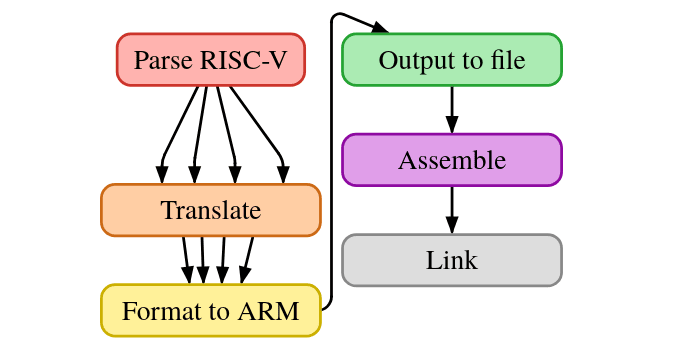

To keep our mapping of registers consistent, we created a look-up table to convert each RISC-V register into its corresponding ARM register.

fn map_register(riscv_reg: RiscVRegister, riscv_width: &RiscVWidth) -> ArmRegister {

ArmRegister {

width: map_width(riscv_width),

name: map_register_name(riscv_reg),

}

}

map_width and map_register_nameCritically, ARM registers can vary in width and RISC-V cannot. For this reason, we added a width argument to this function and decompose the conversion of width and register name into separate functions, map_width and map_register_name. We define widths to be the size of a register and define register names to be the width-agnostic name of the register in assembly (i.e. sp or general purpose register 1).

4.4. Calling Convention

The calling convention of an ISA ensures compatibility with binaries from other compilers (Volume I: RISC-V User-Level ISA V2.1draft, Chapter 18, Calling Convention, 2014). If a program does not interact with foreign functions, then it is not required to abide by the calling convention. This flexibility makes the register translation easier due to less constraints on how Binary Room handles register mappings. To ensure that local register values are preserved between function calls, Binary Room efficiently saves registers onto the stack before a call instruction and restores them from the stack when returning from a function call.

The calling convention constraint still applies to syscalls and dynamic libraries.

4.4.1. Syscalls

We chose to directly translate syscall instructions. Alternatively, we could have taken advantage of the syscall wrappers built into libc (Syscalls(2) - Linux Manual Page, n.d.). However, we chose not to deal with complexities of dynamic libraries, instead directly modifying the instructions which set up syscall arguments and invoke the syscall.

Originally, we thought syscall translation would be equivalent to normal instruction translation. However, there were some nuances that made this more challenging. One such nuance was that syscall numbers change across architectures.

# write(stdout, buf, len)

# syscall number

li a7,64

# arg 2: len

li a2,13

# arg 1: buf

lui a0,%hi(buf)

addi a1,a0,%lo(buf)

# arg 0: stdout fd number

li a0,1

# trigger syscall

ecall

write Linux syscall to write a buffer to standard out.When you want to perform a syscall, you need to indicate which syscall you want to execute by loading the syscall number into a register. In Listing 3, the syscall number, 64, is loaded into register a7. However, this syscall number is defined by the operating system. Linux's syscall numbers vary across architectures and ISA variants (i.e. 32-bit and 64-bit) (Arm.syscall.sh, 2024).

Our initial approach inserted instructions to use a lookup table to convert the syscall numbers. At runtime, this code would look at the requested syscall and rewrite the correct value for aarch64 (Linux Kernel System Calls for All Architectures, 2025). Luckily, Linux shares identical syscall numbers between ARM 64-bit and RISC-V 64-bit. It was sufficient for our architecture pair to directly translate the same syscall numbers without modification.

4.4.2. Branching

Binary Room supports relative branching to labels. We extract labels from the disassembled input binary and map them verbatim to the output ARM binary. This insertion guarantees that the label ends up at the same point in the execution of the translated binary. The assembler handles the complexity of turning labels into addresses. Binary Room does not support absolute branches to arbitrary addresses.

5. Challenges

5.1. ISA Quirks

Instruction sets handle the same primitives differently. For example, RISC-V uses a zero register to produce zero arguments to instructions. In ARM, you must use a normal register or dummy instruction such as xoring a register with itself to get a zero (RISC-V Instruction Set Specifications, 2019).

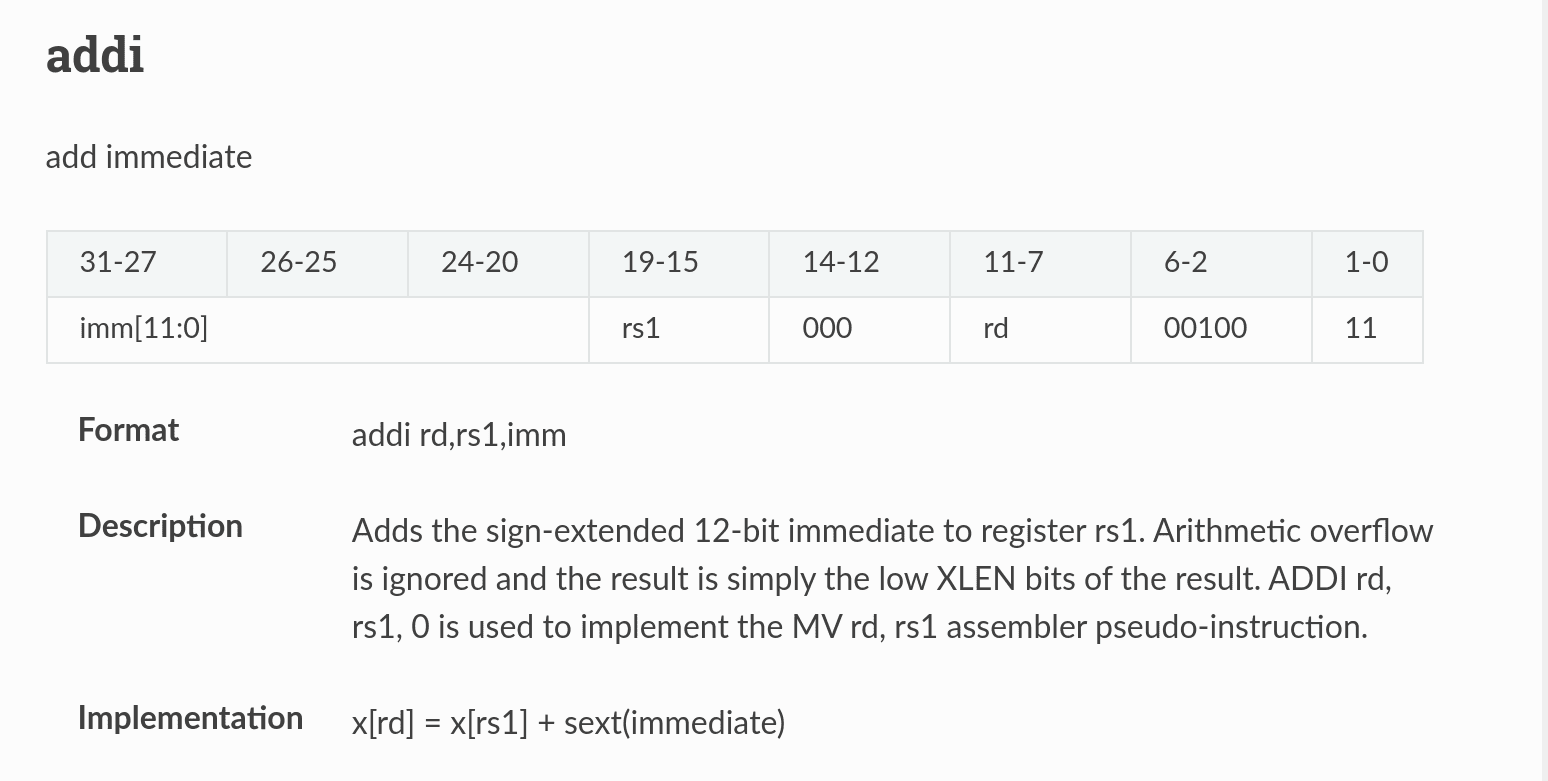

The instruction behaviors also differ between the ISAs. We needed to handle the cases where arguments can change which instruction we need to translate to. For instance, RISC-V's add immediate (addi) opcode can take positive or negative constants, whereas ARM's immediate argument to add can only be positive. Translating this requires handling the different cases of argument values. Sometimes, these translations cannot be determined statically, as seen with syscall numbers.

Figure 3 shows the information provided by the ISA reference. Instructions have high level implementations which authoritatively define their behavior (RISC-V Reference Card, n.d.). This pseudocode enables us to ensure instruction maps have the same behavior.

5.1.1. Pseudo-instructions

Binary disassemblies contain the list of instructions of the program. However, there are also RISC-V pseudo-instructions that can get generated (RISC-V Assembler: Arithmetic, 2024). These are higher level operations that correspond to multiple individual operations. These abstractions are not documented in the architecture manual, so we had to use unofficial online posts to decipher the meaning of these pseudo-instructions.

5.2. ISA Documentation

The largest obstacle we encountered during this project was tracking down relevant documentation and discovering what we needed to know. The general ISAs for RISC-V and ARM are open, but exact implementations of the specifications can differ greatly. For example, when looking for documentation, we would often find incorrect or misleading information. Initially we faced confusion with conflicting information online. This mismatch is because the 32-bit and 64-bit versions of the ISAs change the behavior of registers and syscalls. Instructions work differently on different ISA versions, for instance the many versions and parts of ARM (armv7, aarch64, etc.).

Another difficulty was fully understanding how each ISA works. We needed to understand the semantics of each ISA in order to create a mapping. We found unofficial documentation, such as Figure 3, to be more complete and intelligible than official documentation. Mapping instructions and registers required carefully diffing the register specifications and calling conventions for each ISA. The issues with syscalls led us to decide not to support 32-bit binaries.

As we produced the output binaries, we ended up having to debug invalid assembly. Assembly is itself high level, so we had to deal with linking errors with illegal arguments, unexplainable segfaults, and dealing with OS specific assembly problems such as alignment constraints and extern symbols.

Testing our implementation proved difficult as you need to get everything working in order to test. Each part of the pipeline is dependent on previous parts. Unit testing did not help find bugs as much as running test translations on real programs. Every program you compile with gcc requires dynamic libraries, as there is an implicit libc call to exit the program. We were unable to get static nolibc binaries to work as it has dependencies on the libc provided by the host OS, which needs to be built for RISC-V or ARM.

Another complication is that even simple binaries do not follow the conventions you would expect. For a "hello world" program, we implemented conversion of the text section. Even at minimum optimizations, gcc puts the literal string behind a call to the IO_stdin_used symbol. We decided to not handle all the complications with process and library loading, so a "hello world" program only works with a direct offset to the constant.

5.3. Development environment

Developing Binary Room requires running a Linux machine with QEMU and cross-compile toolchains for riscv64 and aarch64. Binary Room is built with Rust's cargo toolchain and tests run with cargo and some platform-specific build scripting.

To handle the complexity of the build environment, we use the Nix package manager. Nix shells allow us to create a fully reproducible build environment and easily manage parallel compiler toolchains for each architecture we need. (Cross Compiling - Nixos Wiki, 2025)

5.4. Debugging

Debugging the output assembly proved difficult. There are no layers of abstraction below the binary, so there is no debug information when a program goes wrong. Additionally, the issues are typically related to hardware or illegal instructions, so debuggers such as gdb cannot provide any help. We ran into such issues when supporting macOS on our output binaries. macOS has different alignment and linking policies than Linux hosts. Debugging crashes can be difficult as there is not much documentation online explaining these failures. When Binary Room introduced unexpected segmentation faults, we debugged the ARM binary using gdb on an AWS EC2 instance with an ARM-based Graviton CPU.

6. Evaluation

Binary Room provides several programs which it is able to translate. We run translation against all of them by using cargo test. We currently support programs that compute Fibonacci, run arithmetic in a loop, print hello world, and echo stdin. You can view them on GitHub.

6.1. Benchmarking

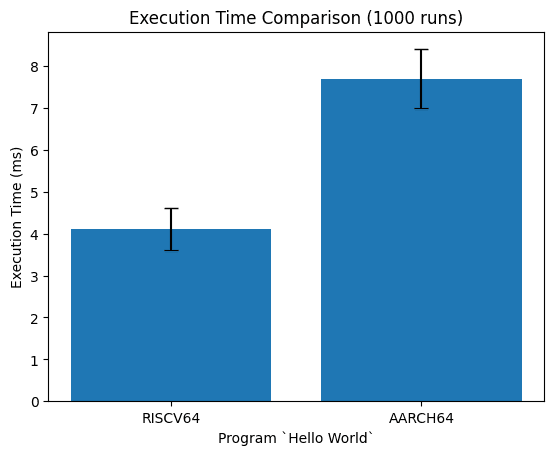

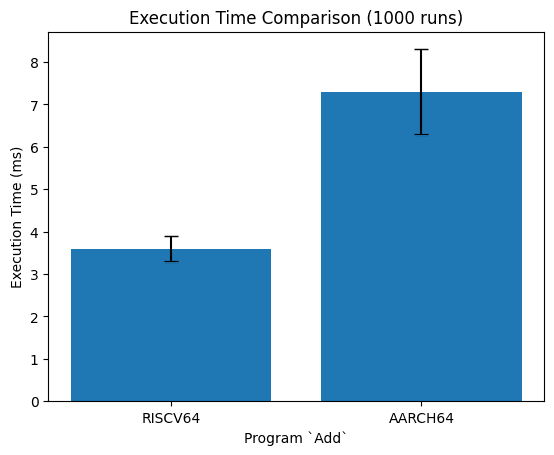

We evaluate Binary Room in comparison with QEMU. We run the original RISC-V and translated ARM assembly via QEMU on a x86 machine. We use 100 warmup trials and then repeatedly run the test program 1,000 times to get the average and standard deviation of runtime.

We find that the RISC-V binaries run about twice as fast, as compared to our translation. We predict most of the runtime is due to overhead from loading the process and QEMU. We do not have access to a riscv64 machine, so we are unable to do a fair comparison of bare-metal results. We find both ARM translated binaries run 88-103% slower in QEMU. We are unsure of the cause of this slowdown as the instruction mappings are near one-to-one, so each program should run a similar number of instructions.

7. Discussion

Binary Room introduces a static binary translator from riscv64 to aarch64. Unlike other emulation options, Binary Room produces a fully compatible binary with no dependencies. QEMU and Rosetta2 require just-in-time runtime support to support their translations. Statically translated binaries are more portable, though we forego optimizations that could happen based on runtime values. Furthermore, Binary Room is written in Rust and natively supports both macOS and Linux targets.

8. Conclusion

Binary Room is open source and freely licensed. You may access the source code on GitHub:

https://github.com/samir-rashid/binary-room

References