Physics of Satellite Internet From First Principles

Published:

Streaming live video by shooting bits through the atmosphere to a hunk of metal racing across the sky at 27,000km/h sounds impossible. Modern satellite internet does this while offering gigabit speeds and latencies competitive with wired connections. How do the laws of physics allow us to engineer systems that deliver this unbelievable service?

This post explains the fundamental principles enabling high-speed satellite internet possible. We will build an intuition for the constraints without hand-waving the physics.

Disclaimer: I am no expert and have no formal electrical engineering background. This post is backed by my readings of nonauthoritative online public resources. I will not be updating this post, so please leave corrections in the comments section.

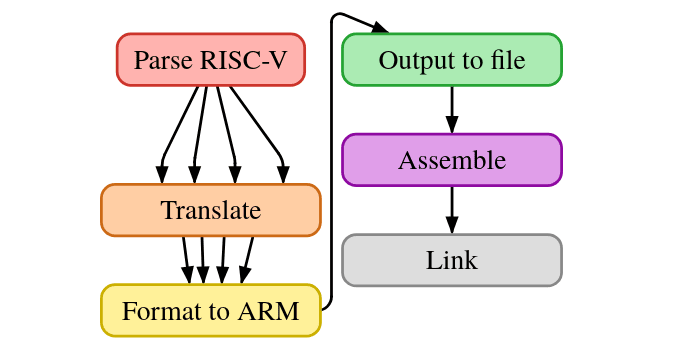

Satellite internet crosses multiple different links to provide connectivity. Users connect devices to a satellite terminal, usually a small dish, that talks directly to a satellite. The satellite may relay data across other satellites before reaching a ground station and the internet. This post focuses on satellite-ground link, though these calculations apply all to wireless connections.

There are two orbits we will look at: low Earth orbit (LEO) and geostationary orbit (GEO). In summary, satellites closer to Earth have stronger signal, lower latency, and require smaller antennas. However, further satellites get more coverage, so a handful of GEO satellites can mostly achieve global coverage, while a LEO constellation requires many more satellites.

The Fundamental Challenge

Imagine shouting across a room–you can only shout so loud and it gets quieter with distance. Satellites have the same issue but from hundreds of kilometers away.

When transmitting a signal, you can think of the energy spreading uniformly in all directions. The power density (watts per square meter) follows the inverse square law:

\[\text{Power Density} = \frac{\text{Total Power}}{4\pi R^2}\]This represents the primary constraint in satellite communications: doubling distance quarters signal strength.

At 1,000km away, the signal spreads over 12.6 million \(\mathrm{km}^2\). At geostationary orbit (GEO) altitude of 36,000km, that same energy covers 16.3 billion \(\mathrm{km}^2\). The antenna in your device receives a tiny fraction of that radiated power.

The inverse square law explains low Earth orbit (LEO) advantages: moving satellites closer from 36,000km (GEO) to 550km (LEO) above the Earth’s surface improves received signal strength by over 4,000 times. The satellite needs to “shout” across 35,450 fewer kilometers. Check out this Wikipedia diagram for a true sense of scale and this post if you need a refresher on orbital mechanics.

Link Budget

Measuring connection performance requires accounting for all signal gains and losses with the Friis Transmission Formula1:

\[P_r = P_t \cdot G_t \cdot G_r \cdot \left(\frac{\lambda}{4\pi R}\right)^2\]Where:

- \(P_r\) = Power received at your antenna (watts)

- \(P_t\) = Power transmitted by satellite (watts)

- \(G_t\) = Gain of satellite’s transmitting antenna (dimensionless)

- \(G_r\) = Gain of your receiving antenna (dimensionless)

- \(\lambda\) = Wavelength of the radio signal (meters)

- \(R\) = Distance between satellite and your antenna (meters)

Decibels (dB) are logarithmic, so they turn multiplication into addition:

\[P_r\text{(dBW)} = P_t\text{(dBW)} + G_t\text{(dBi)} + G_r\text{(dBi)} - \text{FSPL(dB)}\]The Free Space Path Loss (FSPL) term captures the inverse square law:

\[\text{FSPL(dB)} = 20\log_{10}\left(\frac{4\pi R}{\lambda}\right) = 20\log_{10}(R) + 20\log_{10}(f) - 147.55\]Let’s go through each component and its bottlenecks.

Transmit Power (Pt) faces different bottlenecks at each scale. Large GEO satellites can generate 100+ watts per beam but hit thermal limits as it is hard to dissipate waste heat in vacuum. Smaller LEO satellites are constrained by their total power budget from solar panels, limiting power to about 10 watts per beam. Phones trasmit 0.2 watts, limited by battery life and SAR regulations that prevent excessive radio frequency exposure to human tissue.

Antenna Gain (Gt, Gr) measures how well the antenna focuses the signal’s energy. Larger apertures provide higher gain. Satellite phased arrays achieve approximately 35dBi (3,000× amplification) within size and weight constraints. A dish reaches ~38dBi (6,000× amplification) but is bigger and require precise pointing. Phones get ~2dBi (1.6× amplification).

Distance (R): As we know from the inverse square law, this quadratic term becomes the dominant factor in link performance. LEO satellites at 550km altitude experience 173dB of free space path loss, while GEO satellites at 35,786km suffer 209dB loss. This 36dB difference means GEO signals arrive 4,000 times weaker than LEO signals. We will go into the tradeoffs of different orbits near the end of this post.

Shannon Limit

Once you receive a signal, you need to decipher the encoded data. Maximum data rate follows the Shannon–Hartley theorem:

\[C = B \cdot \log_2(1 + S/N)\]Where:

- \(C\) = Channel capacity (bits per second)

- \(B\) = Bandwidth (Hz)

- \(S/N\) = Signal-to-Noise Ratio (dimensionless)

This equation reveals you either need more bandwidth or better signal-to-noise ratio.

More bandwidth (B) linearly increases the data rate, which explains why access to frequency spectrum can go for billions of dollars. Higher frequencies are more susceptible to the weather. LTE is a relatively low frequency (~2GHz), which allows the signal to go through buildings.

Improving signal (S) quality offers diminishing returns due to the logarithmic relationship, but the effect remains significant.

Noise (N) originates from thermal agitation of electrons and is unavoidable above absolute zero:

\[N = k \cdot T \cdot B\]Where:

- \(k\) = Boltzmann constant \((1.38 \times 10^{-23} \ \mathrm{J/K})\)

- \(T\) = System noise temperature (~150K for good receivers)

- \(B\) = Bandwidth (Hz)

Since noise is fixed by physics, improving the Signal-to-Noise Ratio requires increasing signal power–which brings us back to the link budget.

GEO vs LEO Path Loss Calculation

Now we can quantify why lower orbit satellites are transforming satellite communications.

Given a 20 GHz signal (λ = 0.015m):

GEO Path Loss (35,786km):

\[\begin{align} \text{FSPL} &= 20\log_{10}(35{,}786{,}000) + 20\log_{10}(20 \times 10^9) - 147.55 \\ &= 209.54 \text{ dB} \end{align}\]LEO Path Loss (550km):

\[\begin{align} \text{FSPL} &= 20\log_{10}(550{,}000) + 20\log_{10}(20 \times 10^9) - 147.55 \\ &= 173.28 \text{ dB} \end{align}\]Difference: 36.27dB The LEO signal is \(10^{(36.27/10)} =\) 4,233 times stronger than the GEO signal.

This 36dB difference drastically changes system design. LEO’s stronger signal enables higher-order modulation schemes. While GEO systems might use 16-QAM (4 bits per symbol), LEO can use 1024-QAM (10 bits per symbol) at the same error rate. Also, a 19-inch flat panel can achieve what previously required a 4-foot parabolic dish.

Worlds Away

The proximity advantage comes with complexity costs. GEO satellites match the Earth’s rotation, so they appear stationary in the sky and require no tracking. LEO satellites complete an orbit every 90 minutes, demanding rapid beam steering, satellite handoffs, and constellation management.

LEO signals round trip in ~4ms while GEO signals require ~240ms, impacting real-time applications over GEO networks.

Dish vs Phone

How much bandwidth can you actually get from a LEO satellite based on your antenna?

Assumptions:

- LEO satellite at 550km altitude

- 20GHz downlink frequency

- 250MHz channel bandwidth

- 10W satellite transmit power

- 35dBi satellite antenna gain

- 150K system noise temperature

Dish Link Budget:

\[\begin{align} \text{FSPL} &= 153.3 \text{ dB} \\ P_r &= 10 \text{ dBW} + 35 \text{ dBi} + 38 \text{ dBi} - 153.3 \text{ dB} = -70.3 \text{ dBW} \\ N &= 10\log_{10}(1.38 \times 10^{-23} \times 150 \times 250 \times 10^6) = -122.86 \text{ dBW} \\ \text{SNR} &= -70.3 - (-122.86) = 52.56 \text{ dB} \\ C &= 250 \times 10^6 \times \log_2(1 + 22{,}908) = 4.37 \text{ Gbps} \end{align}\]Smartphone Antenna Link Budget:

\[\begin{align} \text{FSPL} &= 153.3 \text{ dB (same)} \\ P_r &= 10 \text{ dBW} + 35 \text{ dBi} + 2 \text{ dBi} - 153.3 \text{ dB} = -106.3 \text{ dBW} \\ N &= -122.86 \text{ dBW (same)} \\ \text{SNR} &= -106.3 - (-122.86) = 16.56 \text{ dB} \\ C &= 250 \times 10^6 \times \log_2(1 + 57.5) = 1.38 \text{ Gbps} \end{align}\]A gigabit to my phone from space!? These calculations assume perfect conditions. In reality, you need at least 10-15dB margin to account for atmospheric losses from rain and clouds, pointing errors as satellites move across the sky, receiver implementation losses from non-ideal components, and Doppler effects from the satellite’s 27,000km/h orbital velocity.

The dish has plenty of margin (52.56dB), but the phone is borderline. This is why a cellular service needs to use much narrower bandwidths.

Real Smartphone Antenna:

Keeping the same frequency with a 5MHz channel instead of 250MHz:

\[\begin{align} N &= 10\log_{10}(1.38 \times 10^{-23} \times 150 \times 5 \times 10^6) = -139.85 \text{ dBW} \\ \text{SNR} &= -106.3 - (-139.85) = 33.55 \text{ dB} \\ C &= 5 \times 10^6 \times \log_2(1 + 2{,}884) = 55.73 \text{ Mbps} \end{align}\]A phone-scale antenna could expect closer to 60Mbps.

Engineering Constraints

Engineers need to navigate the physics to balance trade-offs to make a viable system.

Power Budget

A satellite’s power budget determines beam transmit power.

\[P_{\text{available}} = A_{\text{panel}} \cdot \eta_{\text{solar}} \cdot \cos(\theta_{\text{sun}}) \cdot f_{\text{eclipse}}\]The solar panels need to generate enough energy to power the onboard electronics and are mainly used to power the beams. LEO satellites orbit many times per day, so they need to use battery power for the third of time that the Earth blocks sunlight. Ultimately, it’s the power that determines the size of the satellite and the number of beams and their strength.

Frequency Licensing

Radio spectrum is a finite resource managed by country governments. Spectrum allocation creates fundamental trade-offs between bandwidth and propagation characteristics. Higher frequencies offer more bandwidth but suffer worse propagation losses and weather effects.

| Band | Frequency Range | Applications |

|---|---|---|

| L-band | 1-2 GHz | Mobile services, GPS |

| S-band | 2-4 GHz | Mobile satellite applications |

| Ku-band | 12-18 GHz | Satellite TV, Satellite internet |

| Ka-band | 26-40 GHz | Broadband services |

| V-band | 40-75 GHz | Future high-capacity links |

| 5G n53 | 2.4 GHz | Direct-to-device services |

| 5G n256 | 26 GHz | Shared satellite-terrestrial spectrum |

L-band (1-2GHz) offers excellent propagation through atmosphere and modest power requirements, but provides limited bandwidth. Ka-band (26-40GHz) enables high-bandwidth broadband services but suffers significant rain attenuation that can shut down links during storms. V-band (40-75GHz) promises future high-capacity links but faces extreme weather sensitivity.

Orbital Mechanics

LEO satellites orbit Earth every 90 minutes, creating dynamic coverage patterns. Lower altitudes have less path loss but need magnitudes more satellites to maintain coverage.

Orbital inclination determines coverage zones: polar orbits provide global reach including Arctic regions, while equatorial orbits focus capacity on populated areas but leave polar regions uncovered. Plane spacing controls satellite visibility. Too few planes create coverage gaps, while too many increase constellation complexity and inter-satellite interference.

Antenna Pointing

User terminals must track satellites moving at 7.5km/s. Mechanical tracking systems using motors and gears are expensive, slow to respond, and prone to mechanical failure. Phased arrays enable fast electronic steering without moving parts but require complex beamforming algorithms and hundreds of antenna elements, increasing cost and power consumption. Multi-satellite handoffs demand seamless switching between satellites as they pass overhead, requiring precise timing coordination and careful interference management.

Cost

The cost to deliver one Viasat-3 satellite (6,400kg) to geostationary orbit was $150M aboard an expendable Falcon Heavy. The same rocket type launched to LEO with 56 Starlink satellites (310kg) and can be reused, so the launch costs a reduced $97M. Furthermore, the Viasat-3 satellite costs $420M, whereas each Starlink satellite is below $1M.

Viasat-3 satellites get global coverage with three satellites, while a LEO constellation needs tens of thousands.

Why Now?

LEO constellations are not new–Iridium had a network in 1998. If the physics have not changed in the past quarter century, what has?

Launch Economics

Historically, launch costs have limited access to space. Since the 1990s, the cost to launch payload to LEO has dropped from $20,000/kg to below $2,000/kg. Rapidly reusable Starships promise to reduce costs another order of magnitude. This trend has enabled large LEO constellations to be economically viable.

Satellite Miniaturization

Traditional satellites were custom-built, multi-ton systems designed for >15 year lifespans in a harsh radiation environment. LEO satellites operate within the Van Allen radiation belts where Earth’s magnetic field provides partial radiation shielding. Relaxing radiation tolerance allows satellites to use modern electronics that are decades ahead of radiation-hardened components. This modernization means smaller satellites can deliver more bandwidth and use standard components, enabling satellite mass production.

Phased Array

Originally developed for military radar, phased arrays electronically steer beams and can track and hop between fast-moving LEO satellites. Semiconductor advances have reduced phased array costs such that they are now ubiquitous in new wireless standards.

Configurable Hardware

Software-defined radios can adapt modulation, coding, and protocols through software updates. Digital signal processing no longer requires specialized hardware. Field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs) and digital signal processors enable efficient implementation of advanced techniques like 1024-QAM modulation and adaptive coding.

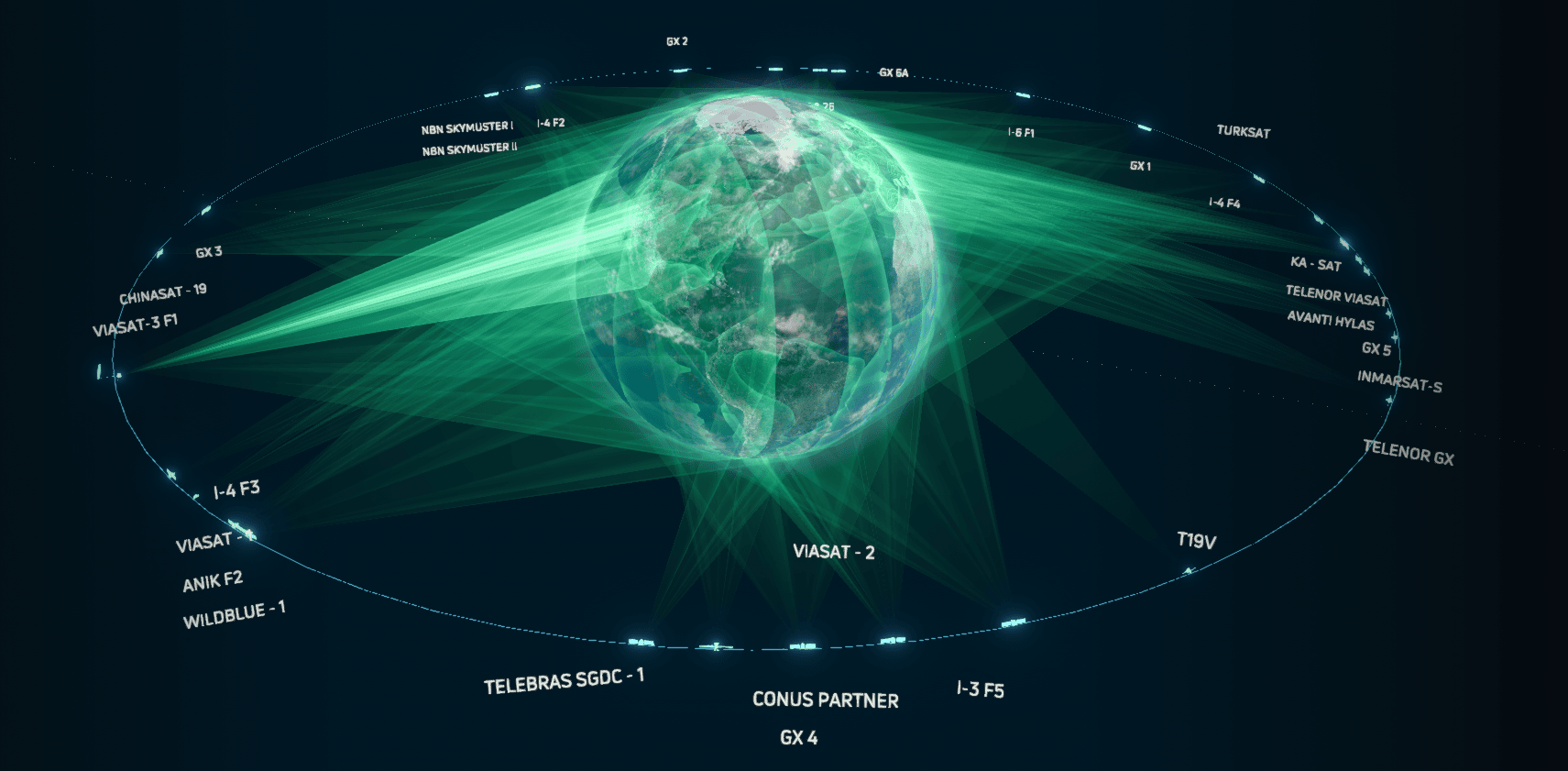

Global Impact

Satellites already provide essential internet to ships and planes and can be used in emergencies after disasters wipe out terrestrial infrastructure. However, there remain over two billion people without internet access. Widespread, low cost, and high bandwidth satellite connectivity offers gigabit internet for the first time to many rural communities, remote islands, and places with undeveloped terrestrial infrastructure.

This post does not begin to get into designing a satellite constellation. There is a tradeoff between wanting global satellite coverage, but demand is not evenly distributed. Viasat has a cool visualization of flight paths and satellite data usage.

The application of electromagnetic theory, information theory, and orbital mechanics bring the world’s knowledge to you no matter where you hike, fly, or sail. This post explored a first principles dive into the terabit cosmic beams that are closing the digital divide.

Further Reading

- Three great satellite constellation visualizers: Viasat, Starlink, and general

- Great intuitive RF Electromagnetics Visualization

- Good slides overview of satcomm

- Taste for how complicated satellite capacity modeling is

- Alright, though outdated series on LEO basics

- Overview of design space of a LEO constellation

- Antenna Theory

- Some background on why LEO internet is succeeding now: Timeline of Spaceflight, Space Launch Market Competition

- MATLAB has some great resources for doing calculations much better than this post

Fun Quiz

What is the least population dense continent?

Estimate the magnitude difference in cost of deploying satellite internet versus fiber optic internet to the above continent. Answer in log base 10 (satellite cost / fiber cost)

For example, if the satellite cost is $1M and fiber cost is $1. \(\log_{10}(1,000,000 / 1) = 6\).

Reveal Answer

Antarctician Internet Cost Estimation

- Population 1,300 (Winter) to 5,100 (Summer) [Wikipedia]

- 181 Polar Starlink satellites [article]

- Overestimate $1M per satellite [Reddit]

- On the order of $181M to serve Antartica Starlink

- Under-sea fiber optic connectivity would cost “upwards of $200M” according to NSF

So the order of magnitude difference is \(\log(\sim 1) = 0\).

Cost of internet is $200k per person! Satellite cost must be paid every ~5 years! (Of course, these satellites do serve other users.)

Sources:

You can read the original paper! Check out Wikipedia and antenna-theory’s derivation. ↩